An Accidentally Virtual Community of Practice

It's hard to believe that I haven't posted a blog since I was in Washington, DC for the American Evaluation Association's Evaluation 2017 conference at the start of November. Like some of you, I sometimes return from conferences sick and exhausted because I've done too much, ate poorly, slept too little, and flown in too many germ-infested canisters for too long with too many sneezing and coughing (lovely!) people. Coming home sick is especially likely during flu season, and boy did I succumb this year. A cold, the flu, then bacterial pneumonia. And I suspect I'm not the only one who has been struggling with my health since our good times in DC.

While being sick for so long was sad and boring, it also pushed my calendar to the limit. For the second time since I started my consulting business in 2011, I had to let a client know I couldn't facilitate a big event we were planning – this time, the first official meeting of a new community of practice for organizations working on post-secondary student success, hosted by The James Irvine Foundation.

We'd had several videoconferences in various subsets and all met in person once before – back in October – to lay the groundwork as a group, but this was to be our first quarterly meeting – and participants, including me, were already feeling bonded, probably because we all have a compelling interest in supporting at-risk high school and college students for the best futures possible, which is a unifying theme if ever there was one in our current challenging educational climate.

Cancelling my participation was a tough call. And of course, my ego kept me from making that call until a few days before the event. Tickets were purchased, hotel rooms were booked, etc. So, onward the community of practice went without me, assuring me by email that they would be just fine. Anything I had to support them was cool, and if I had nothing, that was cool too. They were understanding of my plight and committed to the work, an outstanding combination. (Shout out to uAspire, Students Rising Above, and Southern CA College Access Network (SoCal CAN). And thanks for the sweet card!)

Card from Papyrus.

My ego and I were pretty sure the aftermath of my missing the event would be brutal one way or another. In order to mitigate this brutality, I rallied the morning before and set the group up with a flexible agenda and other tools for writing their charter, structuring a conversation around a pre-determined unanimous field interest, and peer learning. I even assigned one member to take on the task of an afternoon energizer. I assigned facilitators and literally provided checklists. I assigned an icebreaker. I was way hands-on for someone who was going to be accidentally hands-off, and I probably did too much, but I desperately wanted to be there and so I spent the last of my energy imagining I was and putting stuff down on paper and it was pretty cathartic. And then I sent it to the group and slept for four days. There may have been some drooling.

Consulting sages and those well versed in the grounding theory of communities of practice already know what awaited me when I awoke from my slumber.

Me, center, debriefing with community members while picking apples to make fire cider. (Not really -- I actually relied on antibiotics my husband picked up for me at Walgreens.)

Putting Shared Facilitation to the Test

For those not familiar with them, communities of practice are increasingly used in advocacy circles in order to cross-fertilize innovation and best practices. Conceptualized as a model in the late 1990s by Etienne Wenger, communities of practice are currently most in vogue in the fields of business, public health, and education.

Theoretically, communities of practice are paired with the concepts of situated learning and the social learning process, and can be understood as the dynamic interaction between participants' drive for social connection, their motivation for learning, and their investment in shared leadership. For participants, then, the value of membership is found at the intersection of communication, climate, and content.

Of these concepts, the supported emergence of shared leadership has been proven to be not only especially critical but also the least understood and utilized. True shared leadership is a dynamic, highly interactive process that inspires individuals to lead one another so that the group overall achieves goals, breakthroughs, and innovations. Shared leadership contributes to a climate in which all members in the community of practice accept an overall responsibility for the functioning of the community and its ability to meet stakeholder needs.

Naturally, in our previous planning meeting, the group and I explored Wenger's grounding theory, and I particularly underscored the notion with them (and with the funder) that members must have power and leadership even in the design phase of the project.

That may be why they jokingly accused me of pretending to be sick in order to increase their investment. Also why I joked backed that I was going to propose an American Evaluation Association session workshop that put forth "pretending to be sick" as a promising practice for community of practice design.

But there's truth in that joke, I think. In my absence, the group exceeded my expectation. Not only were they able to do ownership-y things like rename their group and complete their charter without concerns about my funder-funded bias guiding them, they also were able to surface and document concerns that I'm pretty sure would have been delayed had I been present. While I've successfully gotten to that level of trust with previous learning communities I've facilitated, such trust doesn't generally happen at Meeting #1. I got out of the way, and it created more authentic interaction. (Plus they finished all of their tasks, and even went through with the afternoon energizer!)

Risks and Rewards

Etienne Wenger. Photo: The Big Learning Event.

This is the second community of practice I've led for The James Irvine Foundation, and I've been appreciative of the risk-taking Irvine has done to ensure that both learning communities were grounded by theory. Wenger's theoretical underpinnings ring true to me as a social scientist and educator, but I've also been involved in communities of practice and learning communities in which unstated convener control is at the center – not in a power-grab way, but because that's the way organizations work. Wenger is an expert on organizational development and theory – so of course, he knew that decentering convener power would be a challenge. Yet, he also predicted that the pay off in terms of field-building innovation and problem solving would be well worth the risk promising.

There are other challenges as well.

Communities of practice tend to go awry when conveners and/or facilitators are not adept at the core conceptual components required for success, and the more often this happens in the philanthropic sector, the less likely participants are to enter the community of practice space in an open and optimistic way.

In other words, nonprofit workers have been burned by "communities of practice" that are neither communities nor allow us to build our practice. Sometimes so-called communities of practice are really time-sucks that have us sitting around a table watching alleged experts that we didn't invite ourselves promote their tool or their program or their cookie-cutter solution. And that makes us surly. (Well, it made me surly back in the day. A lot of people are more patient and nicer than me.)

Still, that's why it is important for the designers and facilitators of such learning communities to plan for and nurture at least these three minimal components for success:

Encouraging a level of investment by all members that leads them to show up regularly, speak up thoughtfully, and prioritize the success of the group.

Developing a structure that makes clear necessary but flexible roles and that supports individuals in determining their own strengths through both self-actualization and feedback from others. (And sometimes, it now seems, through facilitator absence.)

Demonstrating an ongoing commitment to knowledge cooperation (including the co-construction of knowledge) that is co-managed by all members of the community not only through information-sharing but through communication activities such as suspending judgement, persuading, making suggestions, and holding people accountable to the community norms. (This paragraph is full of the prefix "co" for a good reason!)

What I've also learned so far is that supporting investment, flexibility, and cooperation among members is critical but can be challenging: learning community members come from different organizations, are not necessarily bound by the same immediate objectives, and need time to build trust. Yet, building the foundation to support trust is fundamental to the success of the community from Meeting #1. Activities (including active but unstructured time) must strategically support and refresh all three minimal requirements at each interaction and even between. So, my absence was cool – but the tools I provided that supported these "big three" in my absence were even cooler.

Longer-Term Impact of uCANRise

So, yes, I'll stop short of justifying my absence (further!) and calling it a "technique," but seasoned facilitators know how to visibly step back and be hands-off (while staying in the room), and the thriving of the group during my absence demonstrates the value of that expertise. Possibly this is more of an art than a skill – and one that might best be learned by seeing this type of facilitation in action. But it will be interesting to intentionally track such facilitation behaviors to uncover and elucidate more concrete (and feasible) promising practices.

As an evaluator, I'm also looking forward to tracking the longer-term impact of the community of practice – which, by the way, is now officially named uCANRise, a hybrid of the three founding organizations' names.

We don't have a ton of information about the impact of communities of practice operating at this scale and in this sector. However, in the last several years, scholars have documented demonstrated immediate positive impact of communities of practice in the literature. We have seen, for instance, evidence that:

As networking and collaborations increase within the learning community, members perform their jobs more efficiently.

As resources are created and shared within the learning community, site-specific processes improve.

As collective expertise and experience of the community grows, more informed problem solving and decision making increases in the everyday workplace.

We've also got some cool case studies, though most of them are in public health or of internal groups in large organizations. (If you've got case studies of communities of practice that bring together a number of organizations working on the same social issue, let me know in the comments or by email.).

And, of course, with the support of Irvine's amazing Director of Impact and Evaluation, Kim Amman Howard, I'll also be conducting a formal evaluation of this project, so I'll keep you in the loop.

One More Thing: About You

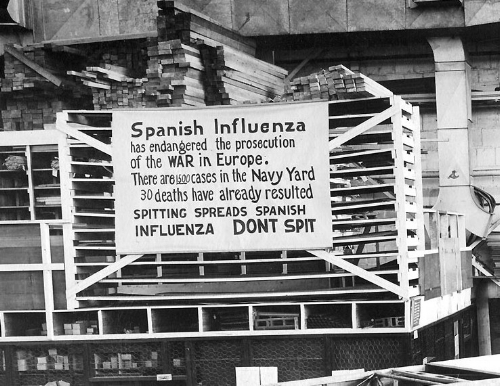

This flu season is awful and apparently we haven't even hit peak yet. My husband teases me about my love of the history of pandemics and my bookshelf full of grim titles in support of that hobby, but we are having a bit of a historical season of the flu here and I can't wait to read about it twenty years from now and recall my small part.

Please stop it with the spitting.

But here's the thing. Generally, when I'm sick -- possibly like you -- I work through. I grew up in Texas, where "walk it off" is a staple of parenting loving advice and care. I have broken both of my ankles at separate times and insisted on walking it off, only going to the doctor days later for one and … Well, let's just say much later for the other. Those bones never came back together because you know what? Walking it off doesn't work for things like broken ankles. Or bacterial pneumonia. Or even this year's strain of flu.

So, I'm sending this message out there to other sole proprietors and evaluation consultants who are working through the flu (especially women because we are the worst at this): Knock it off! Rest, take care of yourself. Don't be ashamed of being sick, or think it makes you look weak. This is a serious flu. Your health is important.

Think of it this way. At the end of your life when you are reflecting on how you lived and what you did, what are the chances that you'll be lauding yourself for prolonging your illness during the flu season of 2017-18, working your immune system to near-death, and infecting your clients along the way? Stay home, push the fluids, nap, drink chicken soup. Go to the doctor if you've got a fever or can't stop coughing. Take care. The world needs you healthy and whole and ready to rock 'n roll.

Laurie Jones Neighbors is an independent consultant and educator who specializes in developing, implementing, and assessing programs and educational experiences in support of equitable political representation and local, regional, and national decision making by low-income communities and communities of color.