Program Evaluation in the Appreciative Context

Early in my consulting career, I spent the bulk of my time providing technical assistance for several "sites" across a variety of different community types throughout California. I arrived on site sometimes because the community had asked for me, and sometimes I was there because someone at the foundation thought it would be a good idea for me to provide my expertise to the group though they had not initiated the ask. Either way (and without asking which circumstances I was in), I'd pack up my markers, sticky notes, worksheets, and case studies and head off to wherever, riding a wave of eternal optimism as my chosen mode of transportation.

Looking back, it was incredibly naïve to think that I could just show up in a community I'd never spent much, if any, time in before and expect the ground team to just roll up their sleeves and dig in to a work plan with me. I grew up in a rural community and now live in San Francisco – I should have known better than to simplify the context. But, I was just so excited about the work.

Coachella

When I showed up in one tiny town in the Coachella Valley, the local site manager told me I was one of a dozen out-of-the-region consultants to show up that quarter alone, and she wasn't having it. In a very small number of words, she suggested I tell the foundation that her site wasn’t in need of my technical assistance. I was sad, but I was also still interested in the Coachella Valley, partly because the landscape and the people reminded me of where I grew up, and partly because I already had a contract to do the work there and wasn’t sure how to handle the situation if I couldn’t follow through. I could envision a power-building opportunity for local residents, and thought my model would serve as a great vehicle for it. But, when the local lead said "No thanks," rather than push her, I asked her if she'd take me to get a date shake.

An hour later, we were in her safely refrigerated car driving around the Coachella Valley, her stopping now and again to point out a local landmark, or pulling over to introduce me to someone through the car window. Having run a successful school board race recently literally through door knocking, she knew everyone and everyone knew her. But to get the best data shake in the Valley, she took me to the edge of town, to a farm stand of a local date farmer. There I met a couple who have one of the oldest date farms in the area and who are much beloved voices in the community. I found them easy to chat with. I talked about my own family farm in what was once Comancheria, and how we'd gone from cattle to sorghum over the generations between my grandparents and me, and how we are currently farming wind.

With my date shake in a to-go cup and heading back to my rental car, the program lead drove past the new high school and told me about how she hoped to engage the new teachers there as part of her site's community-driven strategic plan. I was able to share some of my own experiences of being radicalized by the teaching profession and share a bit about my love of college learners. At one point, the program lead started tailing another car, signaling to it with friendly little taps of her horn, finally pulling in to a parking lot and sliding in beside it. As she leaned in to greet me through my open car window, I met the attorney Megan Beaman Jacinto, and I was blown away by how energetic and rowdy she was for a hugely pregnant woman in 115 degree heat. At another point, my tour guide put on the brakes and did a U-turn to pull up alongside another car, introducing me to a young couple (college seniors home for the weekend) through another briefly open window. They told me about their plans for applying what they were learning at college two hours away to their small community once they graduated.

By late afternoon, what was left of my date shake was warm and soupy and so way too sweet, and I had a much better sense of the community, including the mechanisms of their informal communication style, the cracked car window. And, thanks to this ride-along, key community members at the site had a better sense of me, as did the program lead. We ended up kicking off the work after all, and I still love the Coachella Valley as if I had lived there myself.

Boyle Heights

My introduction to Coachella came to mind last week as I was responding to an RFP for evaluating a capacity-building initiative. I wanted to give an example in the document of an advocacy campaign led by a community advocacy group that contributed to systems change for educational equity. I thought about another one of those foundation's sites, and how one of the local CBOs in the neighborhood had fought to modernize the historic local high school – one of the original sites of the birth of the Chicano Student Movement – and to ensure that a wellness center was in place.

I started searching through documents I could find online that documented the campaign, including how foundational investment took form. One of the things that struck me was the way that the community was characterized in the earliest documents. Someone had clearly conducted a formal or informal Needs Analysis at some point, and the needs data had become the story of the community to show the rationale of the work – and everything else about the community had been backgrounded or even disappeared. The narrative about trauma, mortality, educational attainment, and gangs and crime loomed so large that it covered up many of the things that I know and love about that community – the amazing mutual aid movements that existed well before the foundation showed up, the generations of loving families, the local school teachers who grew up in the community and had actually attended the schools they were now teaching in. If there was an asset analysis, it didn't show up in the narrative. I imagined how angry and bewildering that would be to me as a community member.

City Heights

I flashed back to another technical assistance project I did a couple of years after my Coachella partnership. Mid-City CAN had asked me to come do some work for them in San Diego, and I'd happily obliged. Once again, I packed my consulting go-kit, but I was more mindful this time of the need to build community relationships before whipping out my work plan. Mark and Consuelo were way ahead of me though – they already had a walking tour of City Heights planned. (Well, Mark did. But Consuelo was up for coming along.)

I was wearing the wrong shoes and it was 98 degrees, but off we went, Mark striding in front and Consuelo and I behind, bonding over the heat and our feet. We begged him to stop for shaved ice. Then ice cream bars. I was introduced to Somali cuisine and got an amazing iced Somali chai. And every place we stopped, Mark introduced me to immigrant entrepreneurs and their customers and told me a bit about each storefront and its history in the neighborhood. And all of this was the point – I spent half a day walking around the community, sampling food and meeting people and challenging everything I had read and researched about what is now my favorite San Diego neighborhood.

When Consuelo and I finally convinced Mark to let us stop in a shaded area to rest, I looked out over the park and remarked, "What's with the quarter basketball courts?" Mark's eyes lit up and, while Consuelo and I compared blisters and melted make-up, he told me the story of the quarter basketball courts – which, if you know anything about City Heights, is a very important story about power. By the time we got back to the office, I'd reworked my model in my head and had something much stronger for us to scheme and dream from.

Los Angeles

Back at my desk last week, I pulled out the other to-do I had for the day. I was retroactively sketching atheory of change for a client’s capacity-building program that they'd been running for years. I know, I know – but how could they be running a program for so long without a TOC and logic model in place? Well, not only could they do it, they'd been crushing it. Through an adjacent evaluation, we knew the program was working, but we wanted to be able to explain (to ourselves and others) how it was working. As I stared at my Miro board, I wondered where to start. Because most of my quantitative training was led by an epidemiologist and because I most recently taught in health education (and because COVID-19), I pasted a hypodermic needle at the top of the board to symbolize the program as an intervention (or inoculation), and grabbed the shape tool to make a circle. Then I started thinking about the RFP I'd written that morning.

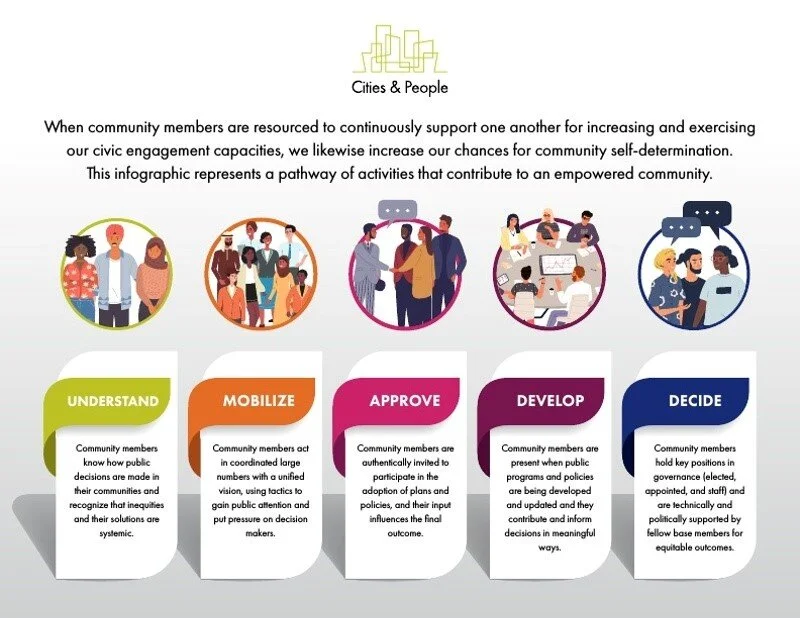

I know the communities and neighborhoods my client works in pretty well. What if I started with what the landscape probably looked like before the intervention? These LA neighborhoods weren't wastelands – movements were born here, cultures were protected and thrived over time. They weren’t just centers of drug addiction, family disruption, high juvenile incarceration rates, and powerless victims of systems of oppression. Rather than rooting the TOC in disparities, I tried rooting it in community power. I’d done that before — documented what I have found to be a common pathway to community power-building — to help funders and donors think about strategic investments. The pathway I modeled, below, supported but was not dependent on investment. How might it be useful as a foundational layer in a theory of change for this or other capacity-building programs?

In every community I've worked in for capacity building, important community organizing activities (formal or informal) could be identified prior to my entrance. This existing work is foundational not only to the way we come in to develop or support programs, but also in terms of the information we need to conduct an authentic evaluation of what we think of as "our intervention." And it is likely to keep happening at some pace and to some scale, whether we are investing from the outside or not.

What Are We Claiming? Whose Work Are We Colonizing?

If our evaluations are going to show us how our interventions work, we need to get clearer on what components are already in place and working before our arrival. If my client's program builds organizational capacity to advance policy outcomes, but local CBOs were already interested in and pursuing tools for policy change, how much of increased capacity can they really claim and how do we measure it? In my example above about the historic high school in Boyle Heights, how should we go about crafting a contribution story that supports learning for future campaigns and power building? In addition to funder, CBO, and student actions, what other factors were in play that have not been accounted for to date in data stories for this campaign?

In the worse case scenario, battle lines are drawn and comms teams weaponized when a “win” is achieved in the nonprofit space. If we are really going to get serious about systems change, we have to get more honest about the true nature of complex change. Designing a theory of change that acknowledges known (and even imagined) pre-intervention and simultaneous contributions to systems change (rather than misrepresenting or engaging in wishful thinking about linear causal chains) would be useful in taking us out of our silos and into the ecosystem of systems change. We need to account for the positive work that is happening without us – that precedes us, that is happening alongside us but perhaps out of our focus, and that, in all likelihood, will continue after we've packed up our worksheets and sticky notes and left.

And Now a Word About Tacos

I'm amused at how personally I took the years-old, needs-assessment informed narrative of a neighborhood I worked in but have not lived in when I was looking for an educational advocacy story for my RFP. I felt quite slighted, from almost 400 miles away. While I know that just 5% of this neighborhood's residents over 25 have earned a four-year degree, and the number of residents in all age groups who have not earned a high school diploma is high by US standards, when I think of this neighborhood, I don't think of gang violence or teen pregnancy or domestic abuse. I think about the incredible community museum that makes permanent the ancestral voices of today's residents, the mouth-watering fish tacos that I need in my belly right now, the mercados on every (not-yet gentrified) corner that serve as sub-neighborhood hubs for networking and communication, the sweet smell of buñuelos, and the long history of community activism and mutuality on this site that is documented back to the mid-1800s but predates European contact. My commitment to this place makes sense because of where and how I entered -- not as an “outside consultant,” but as a whole person.